Cost-effective carbon price pathways: challenging the Hotelling rule

Many countries have indicated to plan or consider the use of carbon pricing. The shape of the carbon price pathway over time remains a topic of debate. Many models assume an exponentially increasing carbon price pathway based on the Hotelling rule. In a recent study, the authors show that this Hotelling rule is in fact not optimal under many plausible assumptions.

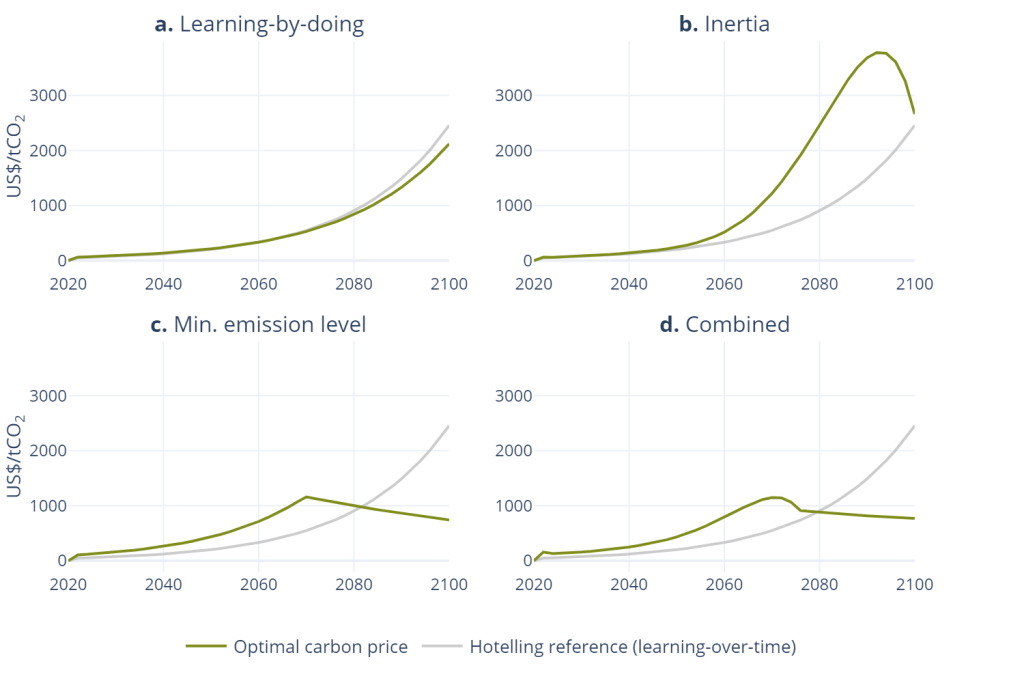

The authors test the robustness of the Hotelling rule by using experiments with plausible assumptions for learning by doing, inertia in reducing emissions, and restrictions on net-negative emissions. Analytically, they show that if mitigation technologies become cheaper if their capacities are increased, Hotelling does not always apply anymore. Moreover, the initial carbon price is heavily influenced by restrictions on net-negative emissions and the pathway by both restrictions on net-negative emissions and socio-economic inertia. This means that Hotelling pathways are not necessarily optimal: in fact, combining learning by doing and the above restrictions leads to initial carbon prices that are more than twice as high as a Hotelling pathway and thus to much earlier emission reductions. The optimal price path also increases less strongly and may even decline later in the century, leading to higher initial abatement costs but much lower long-term costs.

We argue that minimization of mitigation costs by setting only the initial carbon price and letting the pathway be determined based on the Hotelling rule is too simplistic.

Validity of the Hotelling rule

In 1931, the economist Harold Hotelling showed that the optimal price for extracting an exhaustible natural resource should grow at the same rate as the interest rate. More recently, this setting was extended to global climate policy: a carbon budget would be the “exhaustible resource”. Many Integrated Assessment Models assume an exponentially increasing carbon price in scenarios with a carbon budget.

In this paper, the authors show that the Hotelling rule can indeed be optimal, but only under very strict conditions: when there are no limitations on emission reductions and when technological costs only decrease at a fixed rate over time (learning-over-time). These assumptions are however rather unrealistic.

Challenging the rule under more plausible assumptions

In the first experiment, learning by doing, the mitigation costs are reduced as a function of previous mitigation effort. In this setting (Fig. 1a), the initial optimal carbon tax is about 25% higher than in the learning over time experiment, after which it increases less strongly (this is shown analytically as well).

Next, socio-economic inertia (Fig. 1b) is introduced to reflect that energy and infrastructure systems need some time to change and adapt. This is modelled by an additional cost term for reductions exceeding a set reduction speed (inertia rate). Due to this extra cost term, higher carbon prices are required throughout the century. Until mid-century, the carbon price pathway closely follows a Hotelling path. Later, however, the emission reduction speed approaches the maximum possible level leading to a steep increase in carbon price, after which it decreases just before the end of the century.

The third experiment, minimum emission level (Fig. 1c), puts a hard constraint on the amount of net-negative emissions, reflecting the difficulties associated with Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technologies. We model this by not allowing net-negative emissions. Here, the carbon price exactly follows a Hotelling path until emissions reach net-zero, after which emissions remain constant and the carbon price gradually decreases due to technological learning.

Finally, when combining all three aspects (Fig. 1d), the carbon price pathway becomes irregular. Initially, the carbon price is two to three times as high as in the reference Hotelling scenario. By 2070, the carbon price shortly decreases as net-zero emissions are reached.

Conclusions

The study leads to the conclusion that an exponentially increasing carbon tax (as suggested by the Hotelling rule) is not necessarily the cost-effective outcome. In several situations, especially with more stringent climate targets, a higher carbon tax early in the century is cost-effective. Putting it in different words, with ambitious climate targets, the carbon price depends more and more on real-world restrictions, which affect the maximum speed and level of emission reductions.

- Artikel | 1 December 2021to the article on the PBL website